Seven months ago, I was attacked and robbed by two carjackers. They had a gun, and one of them grabbed me from behind. You cannot predict what you will do in a fight or flight situation like this, but apparently, I fight. I managed to get away with only minor physical injuries, but the loss of my sense of safety is with me still. The world is no different than it was before the attack, but, although it is irrational, I have not been able to shake off completely the feeling that this world has turned into a frightening and dangerous place.

It took maybe 24 hours after the attack, after telling my story over and over to various authorities, for the realization to set in that I had heard this story before, maybe 100 times over the past 14 years, from migrants newly arrived at Casa Juan Diego. None of them were carjacked, of course, but they had seen or suffered violence on their journey, mostly violence much, much worse than I had. In that moment, a new insight set in about the importance of our work at Casa Juan Diego, our efforts to help heal the trauma of violence against the migrant persons who come to us.

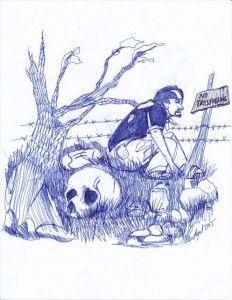

The migration process is filled with life-threatening danger. People fleeing to another country are an extremely vulnerable population. They lack any protection from violence or recourse as they travel across deadly terrain in unfamiliar countries amid criminals and governmental officials who prey on them. Once they manage to get to Casa Juan Diego, the signs of their trauma are pervasive. Some of our guests clearly show their great sadness, others spend their time staring into space. Still others seem all right, but are having a hard time coping. They cannot seem to “stay on top” of their documents and immigration cases, to get their children to bed on time or wash the breakfast dishes before noon, things they must have been able to handle before their journey here. I mean, how hard is it?

Well, it is hard, very hard to focus on the present or the future when your mind keeps returning to past trauma, when you keep thinking about what happened to you and your family in the jungles of Panama, or somewhere off the Ivory Coast, or in the unforgiving deserts of Mexico. For quite some time after the robbery, I was half-present to the world around me. A friend told me that it seemed that I had lost some of my light. Even though I have studied trauma from an academic perspective, it is one thing to hear the stories of violence inflicted and see the resulting post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) that most of our guests have experienced, and a whole other thing to understand the impact of such experiences firsthand.

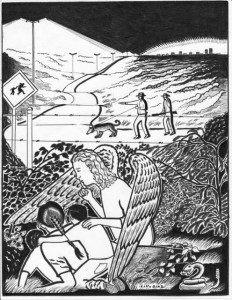

While a few of our guests need professional help to deal with their trauma, what most of them need, and what Casa Juan Diego provides, is a safe, warm, caring, peaceful environment in which they can heal, where they can start to get their lives together in this new land. In other words, we provide hospitality, which is why Dorothy Day, Servant of God, and the co-founder of the Catholic Worker movement, called the houses she founded, “Houses of Hospitality.”

I suspect that most of the friends of Casa Juan Diego who support us so generously do so because we do these Works of Mercy – feeding the hungry, clothing the naked, sheltering the homeless and dealing with their trauma – the physical trauma, of course, but also the emotional and spiritual trauma caused by the violence they have suffered. Certainly, we Catholic Workers spend most of our time doing these things. But at the same time, we emphasize the importance of peace, peace between persons and groups and nations, and peace within our own hearts. The works of mercy and those of peace are interconnected. It is no coincidence that Dorothy was steadfast in her pacifism, opposing all war, even a “just” war such as World War Two. In one of my favorite quotes, she writes that, “No cause, no matter how just, is ever advanced by violence.” She believed that the Scriptures and the teachings of the Church from its very beginnings were very clear in their condemnation of violence, even “good” violence.

It may seem strange when we put it that way, but our culture by and large believes in good violence, redemptive violence, violence of the good guys against the bad guys. In an individualist culture, we are taught that our problems are caused by evil individuals, that the cause of violence is basically those bad guys, the “others” who are not us and not like us. And of course, the only way to counter bad guys with a gun is with good guys with guns.

We are conditioned in our society to see violence from this individual perspective, as individual victims/offenders, and not from a structural perspective, such as the violence that involuntary poverty and marginalization inflict on persons and on their communities. We are conditioned to see violence as either legitimate or illegitimate, depending on whether it is inflicted on someone we identify with or on people we do not like.

Dorothy rejected that dichotomy, totally. “Legitimate” violence, the violence that we say is “ok”, that we tolerate, is not benign. It is intimately interconnected to the “illegitimate” violence that we do not want, the violence that we say is wrong and that we punish, punish with more violence. Dorothy believed that violence is violence, period. And violence begets violence, always.

From a medical/social science perspective, being the victim of violence causes trauma, whether it is the violence of a carjacker, or a drug cartel kidnapper, or that of an economic system that produces increasing inequality between those of us who must sell their labor and those who buy it.

The opposite of violence is peace. Dorothy saw that clearly, hence her commitment to both the works of mercy and her efforts to bring peace through non-violence. In our community at Casa Juan Diego, in solidarity and service, it is easier to see how we are all connected, that our fates are intertwined, in this world and in the world to come. But it is still easy to forget. I have tried since the carjacking to be less frustrated with our guests and more understanding and helpful, giving a kind smile and greeting when returning an unsupervised child to their mother instead of a scolding. Easing away, a tiny bit at a time, their discord and discomfort so that they can heal. Using myself as an instrument of healing, as the prayer of St. Francis suggests: “Lord, make me an instrument of your peace.”

The Christmas season is a powerful time of the year, the season of “peace and goodwill.” I, like many others that have experienced violence this year, have an opportunity to look for a restorative response. Healing and forgiveness instead of anger and more hurt. In our Catholic Worker community, I can see the outcomes of violence and the resulting trauma of our guests in a new way. I really believe that our actions of love and care here somehow transmits itself to the world outside our walls. Every Catholic Worker speaks of this in one way or another; how our meager and often seemingly ineffective efforts at the works of mercy are shared and become magnified. Loving our neighbor creates a powerful force that lives and breathes and travels far. I like to talk about the works of mercy at Casa Juan Diego from the perspective of opportunity. Every encounter is a new opportunity to get it right, to communicate only love, and to value one another. To water the seeds of non-violence and peace. To have the opportunity to experience the restorative power of love, love for others, and for ourselves.

In addition to providing this hospitality to recent migrants who live with us, Casa Juan Diego feeds and provides services to unsheltered or barely sheltered members of the surrounding community. They are mainly single men living on the streets or sharing a small room, trying to work and survive. Many of them are without documents and therefore do not qualify for services that they need.

A subgroup of these men was the initial group that Casa Juan Diego was founded to serve 40 years ago. They came to the United States fleeing the civil wars in Central America, mainly El Salvador. They are in their late 50’s or early 60’s now, but as teenagers and young men they came here to escape being kidnapped and impressed into serving in armies that were killing their own people. Some of them have made it off the streets of Houston and built a decent life for themselves, but others could not. Incapacitated by trauma, they never really had a chance.

Mark Zwick, co-founder of Casa Juan Diego held this group of men close to his heart. Even when he became too ill to work, he insisted on being driven by wherever they were gathered to check on them and to express his care. Since Mark’s death, they have slowly and steadily continued to die as well. The few that are still around are sick and suffering. Many have a diagnosed terminal illness.

In early June, one of them, “Esteban”, a small, soft-spoken man that rides his bike all around the area showed up as usual to our Tuesday morning food distribution. Esteban is dying, thinner every time I see him. Dying of liver failure, according to the doctors in our clinic, but in another sense, dying of being poorly sheltered for decades, dying of the trauma he has suffered over the years. Although the initial source of his trauma happened decades ago, living on the streets inevitably leads to trauma upon trauma.

But perhaps dying of liver failure is not his fate. That particular morning his face was completely black and blue. He told me that his injuries were caused by a fall, but I have seen enough beaten faces to doubt that story. Nevertheless, I was shocked by the severity of his injuries. Luckily, one of the Catholic Workers on duty had some first aid training, and I called her over. She rushed to his side and, with great concern, gently lifted his injured face to assess the damage. Esteban began to cry. Not because he was hurt, but because someone cared.

Esteban may die with nothing and no one, he may already be dead (we tried to get him to go to the ER, but he refused, and I have not seen him since). But for that one moment, someone cared about him.

There have been many moments like this over the years as a Catholic Worker, moments that have changed my life and my heart. Maybe because I am now even more sensitive to violence and the resulting trauma that I am also more aware of how even a small amount of care and concern can lead to healing for even the most wounded among us.

And maybe, in the last analysis, that is really all we do at Casa Juan Diego, both with the guests in our houses, and with the surrounding community. We care.

Houston Catholic Worker, Vol. XLII, No. 4, October-December 2022.