I am often asked what we do here at Casa Juan Diego. My usual answer is we provide hospitality to new immigrants from around the world, which means we live in community together and care for each other. Yet this is just a part of our work; we also serve and respond to the larger immigrant and poor communities of Houston. What a lot of people are wondering, however, is more specific: what do you actually DO?

Every day is different. I thought it might be helpful for me to keep track of what I did in a randomly selected day. Here is the first two hours of that day, and some context to help understand it. The divine and the mundane in all its glory!

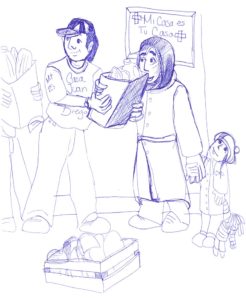

Today is Tuesday, the day of our major weekly food distribution to the food insecure in our community. We expect about 400 families by noon, and many more throughout the week. Our distribution team of volunteers have been working to set up since about 6 AM. We start at 7 AM, beginning with a prayer of gratitude led by Louise Zwick, our director. She prays in Spanish, and a little French sometimes, for the food, the volunteers, for the people already in line, and for the refugees on their way.

It is 7:12 AM, and I check in with Louise. Each Tuesday morning, we catch up on recent events and plan. Today we discuss the status of migrant persons at the border, which determines how many new guests we will need to care for in our houses this week, and what arrangements we need to make, such as alerting our volunteer translators. Recently, most guests have been coming from Venezuela, Colombia, Cuba, Nicaragua, or Africa, but that changes with the situation at the border. Back in the day almost all our guests spoke Spanish, as did all the Catholic Workers, but now we also get speakers of French, Creole, Portuguese, Cantonese, tribal languages of Africa, and more.

Jose, a long-term volunteer, brings us coffee.

After our “coffee conference”, I check in with Kevin, another long-time volunteer who helps to manage the storage and distribution of the food consumed in our houses of hospitality. We are expecting a delivery from the Food Bank later this morning, but Kevin also needs information about how to become a sponsor for a new immigrant. He is eager to help a former guest who wants to bring his family to the US from Haiti.

I check on breakfast for the women and children, to make sure that we are serving a nutritious meal.

While in the kitchen, I refill the hand soap at the hand washing sink. I go through the walk-in refrigerator to check for expiration dates on leftover food (we get inspected by the health department, with no notice) and clean up the general area. I check to make sure that both downstairs bathrooms are clean and have all the needed supplies. I change the kitchen trash, helped by one of our guests to get it out to our dumpster.

It is getting close to 8:00 AM, and the full-time Catholic Workers are eating breakfast with the guests and organizing transportation for the morning appointments – medical, immigration, social service agencies, etc., before praying the Hours. Catholic Workers, referred to as staff, are also volunteers who live in community with the guests. Most are recent college graduates taking a gap year to serve God and the poor, though some Workers have done this for decades. I greet and check in with Marjorie, a recent graduate from St. Francis University in Pennsylvania and a Registered Nurse, and with Kacie, a recent Notre Dame graduate on her way to medical school after her stint as a Worker.

I am “on the door” in the lingo of Catholic Worker communities. It means that we respond to whoever shows up. We listen, empathize, refer, bear disappointment, and diffuse anger at times.

The drive-through food distribution is well underway. The traffic around the house (made even more difficult by the major road reconstruction) is a challenge and I am outside making my first periodic check on the overall distribution of food. There is a holdup in the line – someone coming for food that needs their medication from our clinic prescribed last week. Getting out of the car is a struggle for them so I send them around the block to keep traffic moving, and (literally) run to get their medication as they make it back around.

At 8:16 AM, the first person from the larger community shows up at the door. It is a woman that we know, in a wheelchair and on dialysis, asking for adult diapers, bed pads (we always need these donated!), and Metro Lift tickets. I gather them for her. She needs to wait for an hour for her Metro Lift ride to return so I move her to the pick-up spot in front of our clinic and give her a sandwich, snack, and water (sack lunches are generously provided every week by parishes around the city). She is one of the lucky ones – dialysis is not easy to get without private insurance or citizenship. Our clinic, run entirely by volunteer medical professionals, is free, of course, but we can’t provide dialysis or other advanced medical services.

Back inside, at 8:30 AM, two of my social work students have arrived. Like all Catholic Workers, I am not paid for my work, so my day job is teaching social work at a local University. I generally have 2 to 3 students at Casa Juan Diego completing their field practicum requirement. They are wonderful support to the work of Casa Juan Diego, and, just like the full-time Catholic Worker staff, they leave as transformed people. We check in, and then they are off to start making more food bags for the distribution, coordinating work with the staff, and catching up with our guests.

While inside, I help to supervise for a few moments a child who lives with her mother in our house. Children can’t be in the kitchen and her mother is washing the breakfast dishes, so I am trying to keep her occupied. I am amazed by this child; at 3 years of age, she already communicates in three languages. I think of all she could contribute to her new country if she is allowed to stay. Her parents fled with her to escape female genital mutilation. It is terrifying to think about what will happen if she and her family are forced to return to her country of origin.

The doorbell rings so I’m back on the door. I talk to two people in a row that we really could not help. The first was particularly sad. A woman that is a US citizen, but her husband is not. Only in his late 40s, he has had a stroke and will be coming home soon to little support. We can help with food and some supplies, but I task one of my social work students to dig deeper into what caused the stroke, and to try to find additional resources for this family. It will be difficult. Like many others in the Houston community, despite having lived and worked in the United States for 20 + years, supporting our economy, he doesn’t have a path to citizenship and is therefore ineligible for the services that he now badly needs.

And the second, a young woman looking for rent support to avoid eviction of herself and her children. We cannot come close to meeting the housing needs of the poor in Houston, we can only do what we can. I give her the few referrals that we have to organizations that theoretically might be able to help and encourage her to come for food, and to use our health clinic to save money. This is a hard conversation. I will have several more like it before the day is over.

The mother of a family that lived with us at Casa Juan Diego for many years arrived. As the survivor of a major crime, we helped her to apply for a U-Visa (for crime victims that cooperate with law enforcement), which she received. Now she needs to request her Social Security Card in person. We worked on her application in our library and made plans to go next week to get her card. She is from an indigenous and very poor community in southern Mexico. She is quiet, timid, and soft spoken–not qualities that help you at the Social Security office, so I will go with her.

Louise informs me that we are going to receive someone directly from detention today, so I am on the lookout for the Homeland Security/detention facility van. Sometimes the new arrival, a person entitled to apply for asylum by federal and international law, is locked in a cage in the van. Many times, they don’t really understand clearly why they are being moved, or where exactly they are going. We want to greet them immediately and with kindness so that they know they are safe.

A staff member asks me a question about immigration policy related to a new guest. We talk for a bit about the case and devise a plan of action. As a continuous gift, the staff at Casa are caring, committed to the works of mercy, and hardworking.

Next, I strategize with one of our French-speaking volunteers who is managing the advocacy efforts to get the husband of one of our guests out of jail. We share our frustration and worry about the family. The husband is incarcerated on the US side of the border, held for almost a year, not by the federal government who would release him since he has the right to make his case for asylum, but by the State of Texas. Family separation is a constant trauma that we try our best to navigate and overcome.

I take a two-minute call from my Department Chair at my paying job. I get another cup of coffee. I return an email from an attorney that Casa Juan Diego is paying (at a very reduced rate) to represent one of our guests in immigration court. I respond to a second email from a student about setting up a meeting with me.

Back on the door, I give out a set of cloth diapers and a container of infant formula to a young mother that arrived looking for plastic diapers. For environmental and other reasons, we don’t give disposable diapers, but diapers are an essential need that cost too much money for many people. Our solution is to have high quality cloth diapers and waterproof pants on hand to give out to families. This gives me a chance to make sure that the mom knows about the resources that may be available to her, and how to apply. She does not, so we go over what to do.

It is 9:00 AM and the phone is now ringing on a regular basis. I carry the phone for a bit while Louise is busy: I take one call about the clinic hours, one checking to see if we accept clothing donations (not right now!), another from a person in Central America that we support a bit giving an update on his health.

Back on the door, an unsheltered woman that we know well arrives to the food distribution on foot. Over the years, her mental health, never great, has been declining, and she is often combative, argumentative, and difficult. I have taken to working with her by doubling down with kindness. Giving her all that I think will help her. She can’t always respond in kind, but today she is mostly calm. I give her only the food items that don’t need to be cooked and she leaves without incident. Regardless of her state of mind, she always yells at the top of her lungs, “I love you baby” before she goes. It is 9:24 am. The day is just starting.

There is a mosaic of the Virgin of Guadalupe and Juan Diego at the front door of the main house of Casa Juan Diego. I remember well, ten years ago the two artists, a wife and husband that are responsible for several of our murals, working for what seemed like weeks on the project! We were so eager and impatient to see it. Designing on site, and then cutting and fitting each piece just outside our front door. I still recall the moment when I walked by, when enough of the tiles were in place, and the image became clear.

Sometimes I think about all the people that come to Casa Juan Diego in this way, as all the pieces that make up our beautiful Mother. It helps me to keep going when times are difficult and when the answer is “no” to a tragic and desperate request. We cannot always do enough, really, but it is important to do what we can. As Dorothy Day, the co-founder of the Catholic Worker Movement, puts it, “People say, what is the sense of our small effort? They cannot see that we must lay one brick at a time, take one step at a time. A pebble cast into a pond causes ripples that spread in all directions. Each one of our thoughts, words and deeds is like that. No one has a right to sit down and feel hopeless. There is too much work to do.”

Houston Catholic Worker, July-September 2023, Vol. XLIII, No. 3.