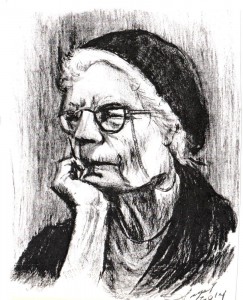

Last fall, political pundits of various stripes informed us that the upcoming 2024 election would be the most important one of our lifetimes. Never mind that we have been told this every presidential election year in this century—this time it was really true. Many of us heeded the warning, absorbed ourselves in the promises of the political personalities and pundits, and in the aftermath, we are learning once again, that electoral politics is at the same time invigorating and dissipating. And it distracts from the real point of our lives which lies beyond politics—at least politics as conventionally understood. To focus on that point, and to gain a needed transcendent perspective on U.S. politics, there may be no better figure than Dorothy Day, co-founder and unofficial matriarch of the Catholic Worker and a Vatican-approved Servant of God, who had the habit of looking at our earthly affairs, as she would say, in the light of eternity.

To get a sense of Dorothy Day’s view of electoral politics, we should take note of the entry in her personal diary for Wednesday, November 4, 1964, the day after election day that year, about what had just transpired: “Johnson elected.” That was it. Two matter-of-fact words. Nothing more.

She could have written plenty. It was one of the largest landslide presidential elections in US political history. It supposedly spelled the end of Goldwater’s brand of hard-right, pro-nuke, political conservatism. It promised to extend the pragmatic liberalism of Kennedy’s New Frontier by building what Johnson had called earlier that year a “Great Society . . . where no child will go unfed, and no youngster will go unschooled.” As a journalist deeply concerned about justice, peace, and world affairs, Dorothy could have written effusively about LBJ’s effort to defeat poverty. But she jotted down none of this. Why was she so terse about the 1964 election?

The answer lies in Dorthy Day’s longstanding, deeply held beliefs about elections and politics, beliefs that she acquired as a young journalist in New York working for two publications, The Call, a socialist daily paper, then later for a monthly periodical called The Masses. Both periodicals were borne out of “the Old Left,” a label referring to a movement in the early twentieth century dedicated to Marxist diagnoses of the injustices in capitalist society and how these can be overcome by revolution and a transition into a classless society. Although this vision may seem outmoded and dangerous these days, it was embraced by leading intellectuals and journalists around the time of World War I, such as Floyd Dell, Max Eastman, Jack Reed, Emma Goldman, all of whom Dorothy knew. She even met Leon Trotsky who she interviewed for The Call in January 1917, not long before he left New York for Russia to be a part of the revolutionary upheaval there on the front lines of the war. Capturing the historical drama of that spring, Dorothy recalled Trotsky telling a crowd at Cooper Union, “Revolution is brewing in the trenches.” When the Revolution came to pass in Russia the next autumn, Dorothy and her crowd—her comrades, she may have said—were enthralled. She forever waxed eloquent about those youthful days when, so they thought, great things were coming to pass in the world. The old order of Czar was being overthrown. A new order was being established, one that that would put an end to the drudgery and deaths of millions of workers and the poor. In Dorothy’s heart and mind, the heroes of the Old Left were the saints and martyrs of today, living for one another, laying down their lives for workers and the poor. And not only in Russia, but in the United States. Eugene Debs, Big Bill Haywood, Elizabeth Gurley Flynn, many others: they all made a deep impression on Dorothy in these early journalistic years.

Dorothy wrote about all this at length in The Long Loneliness, where she also took the time to explain her view among the different intellectual viewpoints that were bandied about in her crowd. She didn’t go in much for the dogmatic Marxists, who believed in waiting for the contradictions of capitalism to play out before launching the Revolution. Nor did she find allies with reform-minded socialists who believed in obtaining a partial measure of justice for workers through mainstream unions, political parties, and the ballot box. Instead, she sided with the radicals of the Industrial Workers of the World, the IWW or “Wobblies,” who opted for direct action to establish the revolutionary society here and now. For Dorothy, this direct-action approach was the most concrete, practical way to fight injustice and forge genuine community.

In short, Dorothy was an anarchist. And not only in her youthful pre-conversion days of the Old Left. She remained an anarchist after her conversion and entry into the Church. Not a bomb-throwing anarchist bent on tearing down society through revolutionary violence, of course. She had become enamored with the Christ of the gospels, teaching us to love our enemies, walking the way of the nonviolent cross, and bestowing on the apostles His gift of peace. She was a Christian, indeed a Catholic anarchist. Thanks to Peter Maurin, she came to see how the Church’s social teaching dovetails implicitly with the IWW’s anarchist vision. The Wobbly slogan, “An injury to one is an injury to all,” can be transformed into our duty to fend for the well-being of all people who are potential members of the Mystical Body of Christ. And the Wobbly adage, “A new society within shell of the old,” can serve as the Catholic Worker’s mission to a world disordered by injustice and needing communities formed by what Dorothy often called “a revolution of the heart.”

In Dorothy’s Catholic anarchist vision, a key part of the collapsing shell of the old society was the state. From her youth she had maintained that the state is a political tool serving the interests of the upper classes, whether it be a monarchy, an autocracy, or even a democracy such as the United States. At the height of the Cold War, Dorothy riled up the readers of The Long Loneliness and of her columns in The Catholic Worker by criticizing the United States for neglecting workers’ rights and the poor at home and for waging imperialist wars abroad. And as always, she matched creed with deed. She refused to pay taxes. She never sought or accepted government money to support the Catholic Worker. She protested U.S. warmaking and was jailed for it several times. And she did not vote.

All of this explains why Dorothy was non-plussed by LBJ’s election back in 1964. As she saw it, electoral politics was not the true path to social transformation, for there exists a chronic disconnect between pulling the lever in the voting booth and pulling the levers of the machinery of the state for the sake of justice and peace. And no amount of investing voting with mystical significance—it is “our sacred duty”—can change it. But if this is true, how do we look at elections, including the most recent one? And how do we chart a path for whatever lies ahead?

I want to suggest three things. First, Dorothy’s anarchism alerts us as to how language is used around election time (which has become virtually all the time) to create the illusion that U.S. politics is based on popular consent. Think of such cliches as “the will of the people,” “free and fair elections,” and “our democracy” as in “we need to protect our democracy.” Such phrases are part of what Noam Chomsky called “the manufacture of consent,” a brilliant, matter-of-fact concept for describing how U.S. politics is presented to us as the result of our choice when in reality our perceptions and desires are already manipulated in manifold and subtle ways by party operatives, advertising agents, management consultants, government bureaucrats, big donors, and television newscasters who welcome into their studios “public intellectuals” to explain the “public affairs” shaping the “public life” of “our Republic.” In other words, we are constantly bombarded with “consensus-fabricating syntax,” as Christopher Hitchens once noted in a book review aptly titled “the ‘we’ fallacy.” His point was that we should be on guard against overusing or misusing the first-person plural pronoun. Stanley Hauerwas has often made much the same point, in a theological and ecclesial sense, by asking, who is the “we”? His point is that there is an identity choice to be made: Is it we Americans or we Christians?

This brings up the second thing Dorothy Day’s anarchism helps us guard against, namely, the partisan captivity of the Church. Catholics regularly decry polarization in the Church, but few see that the problem stems from our near total absorption in U.S. political culture. The absorption process has been underway for a century, but it has accelerated and deepened in the past twenty-five years during which Catholics have roughly split in every national election, though recently they lean more rightward. Until recently, the issues have been sliced and diced along familiar lines: Catholic Democrats are strong on economic justice, racial justice, peace, immigration, and the environment; while conservative Catholics are solid on the life issues, the traditional family, and business. Lately, these alignments have shifted, with Republicans vying for the working class, claiming the mantle of peace, and getting increasingly harsh on immigration. But in any case, extremism has overrun both parties. Thus, Democrats now support abortion with few or no limits and Republicans are planning mass deportations of immigrants. As a result, claims that one party or the other adequately stands for what the Catholic Church teaches have become increasingly implausible. This may seem like an utterly disastrous development for Catholics on both sides of the nation’s widening political divide—that is, for Catholics who fantasized in 2020 that a democratic president would return the Church to its rightful role as the shaper of our “public discourse,” and for those who see the incoming Republican president as the latest opportunity for seizing yet another “Catholic moment.” But the present implausibility of partisan politics actually provides an opening for Catholics who, like Dorothy, do not see consonance but conflict between being American and Catholic, an opening for a more radical approach to what Pope Pius XI called “social reconstruction.”

The third point concerns this more radical, reconstructive approach. As Peter and Dorothy understood it, the word “radical” meant, not just opposing the state, but also going down to the roots of society and taking personal responsibility for social change. This called for translating love into action, which in turn required community. The idea was to forego the politics of the nation-state in order to pursue local forms of community-based work: houses of hospitality and farms, of course, and credit unions, labor unions, neighborhood associations, educational associations, parish pantries, soup kitchens, settlement houses—all kinds of charitable works. With Catholics devoting less time, energy, and money to conventional nation-state politics in the years to come, there will be more time, energy, and money to expand our own charitable works.

Dorothy Day set her sights beyond politics and lived for people beyond politics. She set her sights on God and lived for the people Christ brought to her, the hungry, the thirsty, the sick and imprisoned, the stranger. In the years to come, Christ will continue bringing the poor to us as well—if we receive the grace of setting our sights beyond politics.

Houston Catholic Worker, Vol. XLV, No. 1, January-March 2025.