I live in two worlds. For the past 16 years, I have been serving immigrant communities at the Houston Catholic Worker, offering the Works of Mercy, both Corporal[1] and Spiritual[2] to all that cross our door. My day job is directing the social work program at a local university.

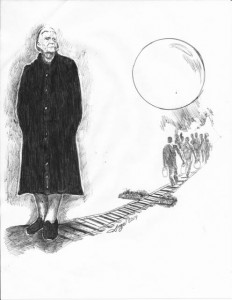

This is a juggling act—the changing of clothes from one setting to the next, trying to remember did I take a shower; did I eat, which language am I speaking? At my University I am important: senior in rank and status with a fancy title and beautiful office, addressed as “Doctor.” At Casa Juan Diego, I am the opposite: small, no office, not addressed by any title (or even my correct name most of the time), not special, not important, not even paid.

This is by design. The Catholic Worker movement is based on a totally different worldview, one that rejects the climb-the-ladder-of-success ethos of both modern universities and social work organizations. Whether in government, non-governmental organizations, or the private sector, most organizations operate bureaucratically – top down, with workers and bosses, workers filling slots on an organization chart and judged by how much they contribute to goals set by the bosses. The work is seen as more important than the workers. All too often, workers are just cogs in the machine and, if the worker can be replaced by robots, computers and/or computer algorithms, so much the better.[3]

This model as applied to organizations tasked with meeting the needs of migrants was arguably not working all that well in the past, but the institutions themselves are now losing their funding support. As programs lose resources and capacity seemingly by the hour (Catholic Charities lost a third of its workforce in Houston last month), the distinction between my two worlds, the decentralized and socially deconstructed Catholic Worker model and the professionalized welfare world has become only too obvious. The “shock and awe” attacks on the budgets and staffing of professional agencies, attacks on their very mission, have stunned their leadership. What worked in the past for them was clearly not going to work in the future.

The Catholic Worker movement started during the Great Depression, another time when the old ways were no longer working. By 1933 the economic system had collapsed and President Hoover’s attempts to deal with the problem was making it worse. Millions of people in dire need of even the basics of food, clothing, and shelter were losing hope. That was the year that Dorothy Day, the co-founder of the movement, opened the first Catholic Worker House of Hospitality.

Nobody thought, then or now, that a Catholic Worker house, or a thousand Catholic Worker houses for that matter, were going to end the Depression. The scale of suffering was just too great. Dorothy believed, however, that we were called to do all we could, in line with what we believed; results were up to God. The beliefs, the core principles behind her actions, were what counted most.

I believe that once again we are in revolutionary times and that our Catholic Worker principles have much to teach our formalized social welfare system about how to understand and deal with the new world we are facing.

For instance, personalism, which emphasizes our individual responsibility for helping others instead of relying so much on the government and other large institutions. Catholic Workers put personalism in action by living a simple life in community, actively working against violence in all forms, performing the works of mercy in whatever context is present. Instead of operating on government funding or grants we rely on the donations of our supporters. All the money that is given to us is used in direct service to others. In our space of freedom, where we take no money from any government or institution, we can build the sort of society we want to see. We can model for others how it would look, and the good that it can do.

This model is also healing for everyone, protects the staff and volunteers from burnout, and has the best chance to promote the conditions of empowerment for those at the bottom of our stratified social systems. At Casa Juan Diego, many different people come to collaborate, and the Catholic nature of our movement is easily expressed by all in the ways that we give priority to the dignity and worth of the human person.

While we do many tangible things at Casa Juan Diego to support asylum seekers, refugees, and other migrants, the most powerful thing we do, something that can only happen in this radically different social arrangement, is to take on, willingly and by intention, some of the precariousness of their lives. This solidarity with the poor is why no one here is paid a salary, why full-time staff share housing and meals with our guests, live in the same conditions and eat the same food, showing them that they are valued and loved. This solidarity is more important now than ever.

And most importantly, in this space of freedom, we can welcome the stranger. This is a power that cannot be taken away, despite the xenophobia of our time. I am reminded in every conversation, and in every act of care at Casa Juan Diego, that this is my country too, and I get to decide how I respond to others. I get to welcome those that the Gospel wants me to love. This ability does not come from the government, but from a much higher power. In our Catholic Worker community, our band of sisters and brothers are as strong and as confident as ever in our commitment to the poor and to the works of mercy. In the Catholic Worker model, we get to dream and build the society that we want to see here on earth, a society based on the good of all.

[1] Feed the hungry, give drink to the thirdly, shelter the homeless, visit the sick and imprisoned, bury the homeless, give money to the poor

[2] Instruct the ignorant, counsel the doubtful, admonish the sinner, comfort the afflicted, forgive offenses willingly, bear wrongs patiently, and pray for the living and the dead.

[3] St. John Paul II’s very first Encyclical as Pope, Laborem Exercens, was released in 1981, one year after Casa Juan Diego was founded. It called for a human-centered approach to economic systems.The worker is more important than their work! This and others of his Encyclicals are well worth reading. http://www.vatican.va/content/john-paul-ii/en.html Click on Encyclicals.

Houston Catholic Worker, Vol. XLV, No. 2, April-June 2025.