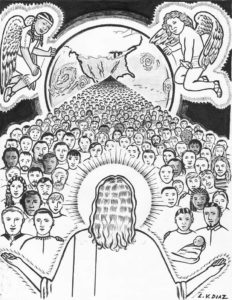

“His blood has made one kingdom out of all nations in the Mystical Body of Christ” – Henri De Lubac

In his January 10th speech to the Vatican Diplomatic Corps this year, Pope Francis reminded them (and all of us) of our common destiny among world crises: “The issue of migration, together with the pandemic and climate change, has clearly demonstrated that we cannot be saved alone and by ourselves: the great challenges of our time are all global.”

In the grand scheme of things, Casa Juan Diego is a small effort— even though hundreds come each week to seek help, a place to stay, medical care, groceries to take home, or a sandwich. We serve the undocumented, especially newly uprooted immigrants and refugees, but more and more, citizens of the US in need of food also come each week.

Casa Juan Diego is an international community, reflecting the richness and diversity of cultures around the world. Our guests who live with us help us to understand the common humanity found in people from all these cultures. Our halls echo with spoken Spanish (with different accents and vocabularies), French, Portuguese, but also native African languages. Our guests who have stayed with us recently have included countless people from Venezuela, but also refugees from Angola, Burkina Faso, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Chad, Cote D’Ivoire, Cuba, Nicaragua, Honduras, and Guatemala. Afghan families are among the many who come for food each day.

The Mystical Body of Christ and Catholic Social Teaching

As we look around and listen and speak with our guests in many languages, we are reminded of the work of Henri de Lubac, SJ, one the great theologians who prepared the way for the Second Vatican Council by retrieving the Sources, especially the early Fathers of the Church. In a dramatic way, De Lubac wrote that we are all one in the Lord: “His blood has made one kingdom out of all nations in the Mystical Body of Christ” (Catholicism: Christ and the Common Destiny of Man, Ignatius Press, 1988, 42). Reminding us that St. Athanasius wrote of how “God made man in his own image,” De Lubac clarified even further that “the divine image does not differ from one individual to another, in all it is the same image” (29). All are members or potential members of the Mystical Body.

De Lubac and the Fathers tell us that “Humanity is one, organically one by its divine structure; it is the Church’s mission to reveal to man that pristine unity that they have lost, to restore and complete it” (51). We hope at Casa Juan Diego that we can contribute our mite to the mission of the Catholic Church in this revelation and restoration of unity and respect toward all. This means that when a migrant in need shows up on our doorstep, it behooves us to recognize the divine image and give that person the respect that God demands of us, even if we cannot do everything the person might request.

Referring to St. Augustine’s commentaries, De Lubac states “No one has the right to say with Cain: ‘Am I my brother’s keeper?’ No one is a Christian for himself alone.” Some of the great women saints of the Middle Ages are featured by De Lubac as well: Mechtilde of Magdeburg, Angela of Foligno, Catherine of Siena, in their prayers and concerns for people of all nations and the peace and union of Christians (244-245).

Not Only Migrants

The pandemic has changed the lives of working people and hurt livelihoods of so many around the world, especially those “essential” workers who each day face not only the possibility of becoming ill with COVID, but have to work under the difficult circumstances of staff shortages and the resulting pressure on those who are able to work. Many already barely eking out a living have not had sick leave, have lost jobs, or have felt pressured to return to work even when ill. This is related to a new phenomenon called The Great Resignation, in which many who can are walking away from their employment. While many have struggled to survive, others have become even more fabulously wealthy or have become billionaires, even lining their pockets with money given by governments to help the workers. Already existing but growing inequality has brought frustration, desperation, sometimes bitterness, and a search for whom to blame, often misdirected.

Climate change is also changing many people’s lives. Droughts, hurricanes, and extreme temperatures have uprooted millions of refugees and migrants who are now stranded in places previously unknown to them. Climate change also is changing the lives of those who have tried not to leave their homes, but who suffer destruction from tornados, historic floods and fires, and extreme temperatures in the United States and around the world.

The Fallen Idol

The economic and social crises and disparities did not begin with the pandemic or climate change. The roots of inequality and the social unrest related to it can be traced to the reigning economic theory of the last 40 or 50 years. Economics professors and politicians embraced “neoliberalism,” known in the United States as neoconservatism. This ideology emphasizes absolutely free markets, trickle-down economics, individualism, efficiency, competition, privatization, deregulation, and a disregard for the lives and welfare of workers. Businessmen who follow this model often publicly scapegoat immigrants, at the same time as they hire the undocumented at very cheap wages for their own gain. Unfortunately, the riches the “trickle down” has created among the very wealthy have never trickled down; they have trickled up. The neoconservative/laissez faire model has encouraged not only moving businesses to poor countries to avoid labor unions here and seek ever cheaper labor, but also coups against governments who defend their workers and do not support the U. S. business model. It is a scandal that Catholic neoconservatives have also endorsed this model.

Peter Maurin and Dorothy Day always spoke of building a better social order. A good place to start in this effort would be reading the Gospels and the teachings of Pope Francis as well as a new article in Commonweal (January 3, 2022) by Anthony Annett, “The Fallen Idol: A Catholic Alternative to Neoliberalism.”

Dorothy Day spoke of robber barons of a previous age. Dorothy said, “We are told, and we try always to keep a just attitude toward the rich, but as I thought of our breakfast line, our crowded house with people sleeping on the floor, when I thought of cold tenement apartments around us and the lean gaunt faces of the men who come to us for help, desperation in their eyes, it is impossible not to hate, with a hearty hatred and with a strong anger, the injustices of this world” (The Catholic Worker, April 1937). The billionaires of today are today’s robber barons.

We wish we could change the whole world –and we do have a responsibility to the whole world, but we work according to the Little Way of St. Therese. As Dorothy wrote in The Catholic Worker in February 1940, “What we do is very little. But it is like the little boy with a few loaves and fishes. Christ took that little and increased it. He will do the rest. What we do is so little we may seem to be constantly failing. But so did He fail. He met with apparent failure on the cross. But unless the seed fall into the ground and die, there is no harvest.”

It would not hurt, however, to ask professors of economics and politicians to read about Catholic Social Teaching.

Houston Catholic Worker, Vol. XLII, No. 1, January-March, 2022.