We were inspired by a sermon on St. Patrick’s Day this year at St. Patrick’s Cathedral (online at 6 a.m. on weekdays) as the celebrant of the Mass reminded us of how the patron saint of a place looks out for the people of that parish or other place named for the saint, from heaven. With this reflection we realized anew how much we count on the support and prayers of Saint Juan Diego and Our Lady of Guadalupe at Casa Juan Diego.

We Chose the Name Casa Juan Diego

Juan Diego’s name was chosen for our work by Mark Zwick when we began. It was over 20 years later when Juan Diego was declared a saint.

Why Juan Diego?

Why did we choose Juan Diego as our patron when we started Casa Juan Diego?

The bigger question–which is really the answer–is why did God choose Juan Diego to be the recipient of the apparitions of Our Lady at the foot of that hill of Tepayac?

The response of many Americans may be, how odd of God to choose Juan Diego when there were so many respected people to choose from. Wasn’t it strange that God would choose a Native American without a college degree or a master’s degree in theology as the messenger to evangelize the local Bishop about the importance and dignity of the indigenous? Wasn’t it strange that he did not send Mary directly to the bishop? What a symbol Juan Diego was and is for those who are nobodies in the eyes of the powerful but are greatly appreciated by God.

As Mark said, the Blessed Mother always seems to be sneaking in the poor uneducated people or children for honors, witness Fatima, Lourdes, etc.

The message of the apparition of Our Lady of Guadalupe was in the messenger, Juan Diego. The chosen one was poor, without formal education, did not speak Spanish, and was one among the race of people not accepted by some of the conquering conquistadors as human beings or having souls.

Our Lady of Guadalupe changed all of that when she sent Juan Diego to the Franciscan Bishop.

Why Casa Juan Diego in Houston?

Forty-two years ago we started the Houston Catholic Worker, possessing nothing except our patron, Juan Diego–and what could he do for us, anyhow?

It was a perfect match. Juan Diego was poor, powerless and a nobody in a worldly sense and so were we. So were the people we would serve who were sleeping in cars in the used car lots on Washington Avenue, refugees from the wars in El Salvador, Guatemala and Nicaragua. We, too, were nobodies as we began taking in refugees in the early 1980’s.

The immigrants and refugees who came and continue to come to us with only the shirts on their backs are wanted by many only for their work, but are not considered human beings by many, just as the first Juan Diego was so considered. Like Juan Diego, they do not speak the language and have no rights.

The priest who blessed our first poor building, the ugliest building in Houston, remarked that we would need $40,000 (in 1980 dollars) to begin. We had nothing, but we did have experience and wobbly faith—all worried about liability and that stuff.

We did not have a penny.

The financial support was forthcoming. A Westside pastor gave us our first check. A young mechanic who lived in our neighborhood asked if he could do something. He went into his house and returned with five one hundred dollar bills. We were on our way.

Since this beginning countless people and other parishes have helped us to be able to respond to the hundreds of people who come each week to seek help, not only for refuge, but for food or medical care.

Our Lady of Guadalupe Appeared in the Darkness

Juan Diego was one of the few indigenous people who had converted to Catholicism during the time of the cruel conquistadors. It was a very dark time, and most of the Native population was not convinced about any good intentions of the conquerors or, by association, their faith.

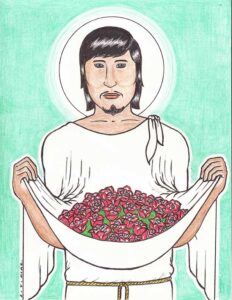

One day Juan Diego, a fairly new Catholic, was walking along at the foot of the hill of Tepayac. He was amazed to hear beautiful music and to see a beautiful lady who spoke to him in loving terms. It was Mary, who appeared to Juan Diego as a brown-skinned Aztec princess and spoke to him in his native tongue, Nahuatl. the language forbidden by the conquistadors, She had a mission for Juan Diego.

The Lady asked him to take her message to the Bishop of Mexico. Juan Diego begged her to send someone else, someone noble, someone well-known and respected. He did not think the bishop would listen to him or believe him. But she convinced him to go.

Juan Diego went to visit the bishop. After several people who worked at the bishop’s office ran interference for a while, the bishop listened, but found it hard to believe what Juan Diego was telling him about the appearance of the Lady from Heaven. He asked Juan Diego to bring him a sign to verify the truth of his words.

Juan Diego returned to Our Lady and told her the bishop had asked for a sign. She told him to go the next day to the top of the Tepayac hill, cut the flowers he would find growing there, and bring them to her. When he went there, he was amazed to find beautiful flowers in that rocky place. He gathered them in his tilma (a cloak similar to a Roman toga) and took them to Mary. She received the flowers in her hands and then placed them again in his tilma, asking him to take them to the bishop as the sign. She cautioned him to show them to no one except the bishop

Juan Diego had trouble getting to see the bishop again because the men around him were suspicious and refused to let him in. When Juan Diego did see him and showed him the flowers, the roses fell on the floor and the bishop and those around him saw the image of Our Lady of Guadalupe imprinted on his tilma.

The Image Imprinted on Fragile Amate Cloth is Still at the Basilica and Intact

The Image Imprinted on Fragile Amate Cloth is Still at the Basilica and Intact

Juan Diego’s tilma with the image of Our Lady is still in its place of honor in the Basilica of Our Lady of Guadalupe in Mexico City. where Our Lady had asked that a church be built. The church has been rebuilt over the centuries, but the tilma is still there. Painters and even representatives of Kodak have examined and investigated the image over the centuries. They have all declared that no painter could have painted that image. No one has been able to explain how the image came there except through the events recounted by Juan Diego. The amate cloth on which the image is printed usually only lasts thirty years. Whole books have been written about all the symbolism contained in the visual details imprinted on the tilma.

The Dark Time of the Appearance of Our Lady of Guadalupe

At the time of the conquest and colonization of the Americas when Juan Diego lived, many of the invaders thought the indigenous people did not have souls and that therefore did not have the right to own anything but should be subject. They were treated badly and enslaved. They were forbidden to speak their own language. (At least in Spanish-speaking countries, as Mark Zwick said, they were still alive, whereas in the United States few Native Americans survived.) With the conquistadors, however, also came missionaries who wanted to share their faith with them. It was hard going because of the terrible treatment the people were receiving. Only a very few natives had become Christian.

Franciscan missionaries who worked hard to share their faith with the indigenous people defended them, during this time before Our Lady’s appearance, writing to the king of Spain and to the Pope to argue that they were human beings with souls. When they wrote, the missionaries described the cruelty, the corruption and hardness of heart of many of their own countrymen towards the people.

One of these Franciscans was Juan de Zumárraga, Bishop of Mexico. Parts of Bishop Zumárraga’s letters to King Carlos V of Spain are reprinted in a book in Spanish by Eduardo Chavez Sanchez, Juan Diego’s postulator. The book is called Juan Diego, una vida de santidad que marcó la historia (Mexico City: Editorial Porrúa, 2002). The quotes below have been translated from that book.

Sometimes the story of Mary’s appearances has been told as if there were no receptive Spaniards at all. Chavez’ book shows how the apparitions were an encouragement for and working with the already existing efforts of some of the missionaries.

Chavez recounts how as the people were enslaved and their women taken by soldiers, the people came weeping to the bishop, who denounced the behavior in his weekly sermons where conquistadors attended Mass. The bishop complained that Hernan Cortés and his men fled from his sermons, no longer going to church. Because of his strong critique of the injustices, cruelty, thievery and corruption especially of those in charge of the Government of Mexico City, Bishop Zumárraga was threatened and lies were made up about him to discredit him and to try to have him replaced.

In 1529, one year and four months before the apparitions of Our Lady of Guadalupe to Juan Diego, Bishop Zumárraga wrote to the king to tell him that the situation was so bad that only a miracle of God could save the situation and the earth: “si Dios no provee con remedio de su mano está la tierra en punto de perderse totalmente.” The missionaries prayed for a miracle.

God Provided the Miracle

Shortly thereafter, God did provide through Mary, the Virgin of Guadalupe, the remedy to what might have been the total destruction of a civilization and culture. One of those who had become Catholic was Juan Diego, who with his wife had been baptized and frequently received the sacraments. (By the time of the appearances, Juan Diego was a widower.) Devotion to Mary, the mother of Jesus, the Mother of God, was very much a part of the evangelization in Christ which Juan Diego had received.

Our Lady appeared to Juan Diego, speaking Nahuatl, and sent him to bring God’s message to the bishop, and through him, to all of us, leaving her own image, pregnant with the child Jesus, on his tilma as a sign of new life.

When she appeared to Juan Diego to ask Bishop Zumárraga to build a church in her honor, the Señora del Cielo, as Juan Diego called her, affirmed the dignity of an oppressed people in an unmistakable way.

Bishop Zumárraga’s Testimony

Bishop Zumárraga’s correspondence to Spain and to Rome after the appearance of Our Lady of Guadalupe reported that a great event had taken place. As Chávez writes, “The light of the Star of the Evangelization was revealed as a moment of intervention of God in human history. If human persons, in spite of the divine intervention, continued with their limitations, infidelities and betrayals; there is no doubt that immediately after the date of the apparitions a marvelous change in regard to the conversions of the indigenous and the change of attitude of the Spaniards took place. A change in the depth of being of the inhabitants of Mexico.”

Written sources from the time of the apparitions confirm “…the great numbers of natives who asked for baptism after these first years, and in this moment, inexplicably, by the thousands: Those baptized by each of these was more than a hundred thousand…’ Motolina, one of the early writers, continued counting the thousands and thousands who had been baptized and arrived at the conclusion that the total for the year of 1536, would be ‘until today the baptized are about five million.’”

Fray Gerónimo de Mendieta, (Historia Eclesiastica Indiana) wrote that by the roads, mountains, and deserted spots a thousand or two thousand Indians followed the religious, just to go to confession, leaving behind their homes and properties; and many of them pregnant women, and so many that some had their babies on the way, and almost all carrying their children on their backs. Other elderly people who could hardly stand even with a supporting stick, and blind people, walked 15 or twenty leagues to search for a confessor. The healthy came thirty leagues, and others went from monastery to monastery, more than eighty leagues. Because on every side there was so much to do, they found no entry. Many of them brought their women and children and their little food, as if they were moving to another area.

The numbers seeking baptism were so great that the missionaries stopped the baptisms for a time to write to Rome to ask how to proceed in such an unprecedented situation.

Juan Diego’s People Were Treated as Migrants Are Treated Today

Vast numbers of the poor of Latin America embraced Our Lady of Guadalupe and they still do. They know, through her, the mother of Jesus, that in spite of their poverty, they have great dignity and that God loves and respects them. Would that those who make economic and military decisions based on flawed philosophies could also realize it. What is taught in university business courses (including Catholic universities) comes from secular philosophies which over the last few centuries have upended the teaching of the Church from the Fathers of the Church through St. Thomas Aquinas and beyond. These newer philosophies, taught in business schools across the world, have presented that which was considered vice and sin, incredibly enough, now as virtues. The result has been a dehumanization of the poor and immigrants and refugees around the world. The poor and migrants today are considered by many as if they did not have souls or even humanity. Perhaps only emerging markets.

Pray With Us For the Intercession of Saint Juan Diego and Our Lady of Guadalupe

Let us ask Saint Juan Diego and Our Lady of Guadalupe to pray not only for indigenous peoples today, but also for immigrants and refugees who often are treated like the Juan Diegos of his time.

As Eduardo Chavez said, “Our Lady of Guadalupe is for all people, however, especially all of the Americas.” In his book Chavez sings of the meaning of her appearances and what Saint Juan Diego means today: “Juan Diego continues spreading to the entire world the great Guadalupan Happening, a great message of peace, of unity and love that continues to be transmitted through each one of us, converting our poor human history, full of tragedies, betrayals, divisions, hatred, wars, in a marvelous History of Salvation, because in the center of the sacred image, in the center of the heart of the Most Holy Virgin Mary of Guadalupe is found Jesus Christ Our Savior. It is precisely she, the Mother of God, our Mother, who presents her son Jesus Christ, brings him to us among flowers and songs, robed in the sun, dressed in stars, standing on the moon, among the clouds like a great treasure who comes from the invisible and which in her is made visible. It is she who, choosing a humble native Indian, Juan Diego, who had had little time to embrace the faith, invites us to embrace our God and Lord.”

Recommended Reading

The Houston Catholic Worker recommends the books below, one on Our Lady of Guadalupe and Saint Juan Diego. The other two explain the devastating effects of errors in standard economics and business practices today which contribute to the attitudes toward immigrants and the poor similar to that toward the people of Juan Diego in his time, These books present more just alternatives from Catholic Social Teaching.

Antony Annett, Cathonomics: How Catholic Tradition Can Create a More Just Economy. Georgetown University Press, 2022.

Massimo Borghesi, Catholic Discordance: Neoconservatism vs. the Field Hospital Church of Pope Francis. Liturgical Press, 2021.

Eduardo Chavez, Our Lady of Guadalupe and Saint Juan Diego: The Historical Evidence. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2006.